Software engineer and cellist Scott McCreary. Photo credit: Scott McCreary

The demographics are inescapable. After decades of low birth rates in North America, Europe and much of Asia, the global work force is shrinking. By the year 2030, it is projected that companies will be 85 million positions short. They will be looking for, and not finding, suitable employees.

With the present concern over robots and AI taking jobs from human beings, it’s tempting to downplay this forecast. But the largest companies, and the organizations that serve them, are paying close attention. So what to do?

Immigration reform, family-friendly policies and intensive skills development will all make a difference in the long term. However, the most immediate solution is to hire overlooked talent—from populations not well represented, or with backgrounds so unusual that they raise a corporate eyebrow.

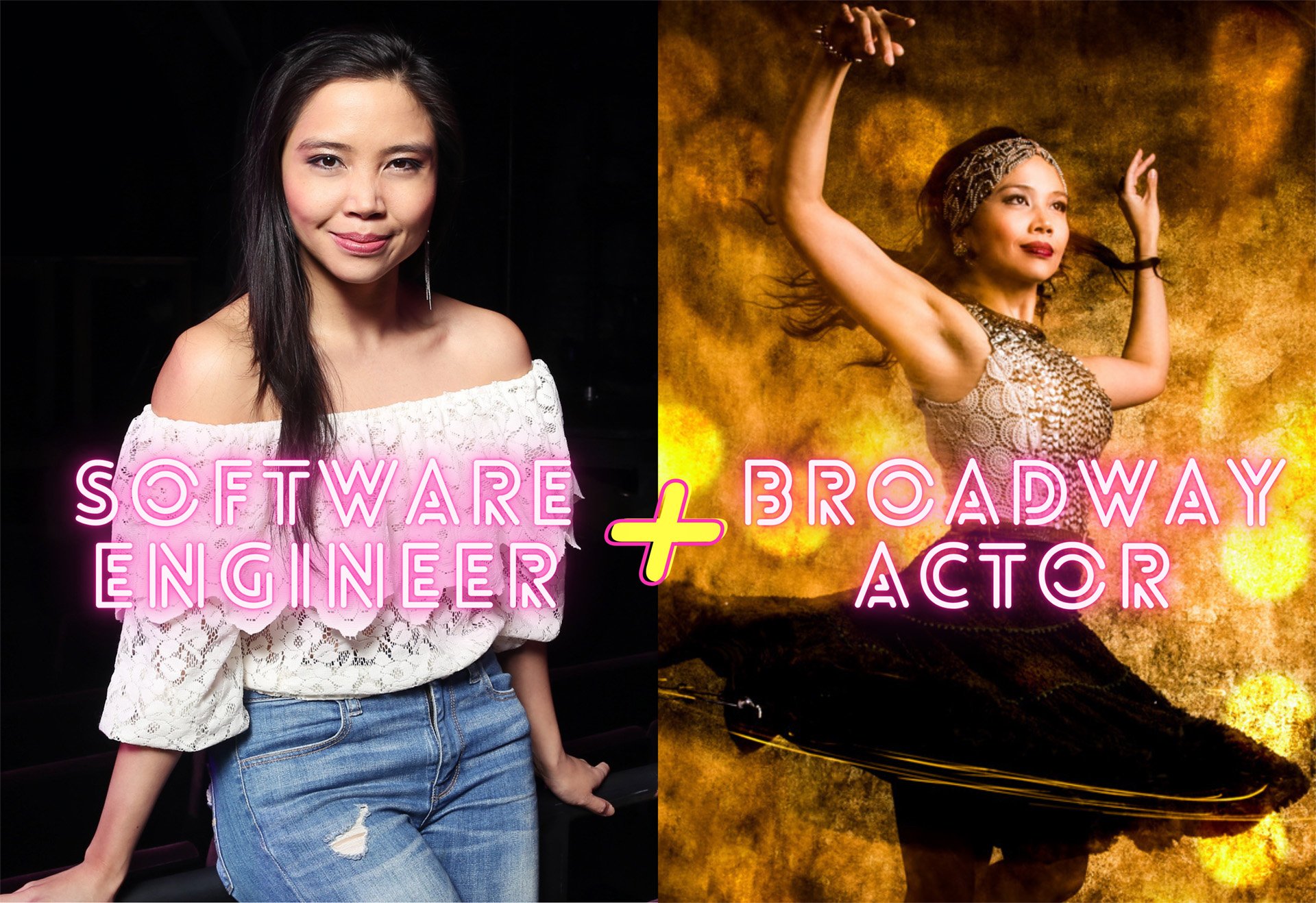

In March of 2020, as the pandemic shuttered theaters, concert halls and performing arts centers, Scott McCreary and Catherine Ricafort McCreary launched Artists Who Code, an online community that helps professional artists make the transition into the tech industry. McCreary and Ricafort McCreary, who are married, had performed on and off-Broadway as dancer, singer and actor (Ricafort McCreary), and cellist, singer and actor (McCreary), for many years. Wanting financial stability and a more predictable schedule, they enrolled in coding bootcamps in 2018. By 2020, both were working full-time in tech.

“Artists Who Code is a volunteer collective of like-minded enthusiasts for art and technology,” explained McCreary, now a senior software engineer at Vannevar Labs, in an interview. “We started it at the beginning of Covid because we saw our friends in the arts losing their jobs, and we wanted to provide a community for them to make the same journey from the arts to tech that we had taken.”

The challenge of explaining transferable skills

Artists have many of the professional qualities that companies desire—focus, discipline, creativity, emotional intelligence, attention to detail—but a frustration with effectively translating those qualities from the arts to another field is often the first hurdle to landing a corporate position.

Other under-represented populations in the workforce face a similar challenge, according to Wendi Safstrom, President of SHRM Foundation. When veterans transition to civilian jobs, for example, they can struggle to express the value of what they learned and accomplished in military service.

Wendi Safstrom, President of SHRM Foundation, speaking at SHRM’s Volunteer Leader Business Meeting (VLBM) November 2023. Photo credit: SHRM

Certificate programs like SHRM’s “Veterans at Work” are designed to help human resource professionals understand those particular skills and how they can be applied to the world of work. But structural barriers remain an obstacle.

“It means changing up your talent management strategy, such as how companies create job descriptions, how they’re using technology to pre-screen resumes, to make adjustments so that people aren’t inadvertently left out of the equation,” said Safstrom in an interview. “While it takes a little effort to shift your hiring practices in order to make this happen, the investments in the short term will pay off dramatically in the long term.”

When Catherine Ricafort McCreary was first applying to tech jobs, even the design of an online form could get in the way. She remembers the user interface at one corporate website not allowing her to input a start-date and end-date with the same calendar year. The company apparently assumed that any position worth including on an application should have been held for more than twelve months.

Software engineer and Brodaway actor Catherine Ricafort McCreary. Photo credit: Catherine Ricafort McCreary

“In the arts, listing all the shows that I’ve done, it’s like a trophy case,” said Ricafort McCreary, now a software engineer at Stitch Fix, in an interview. “But whenever I would bring a resume like that into the corporate world, I’d get reactions like, ‘Why couldn’t you hold onto that job? Why didn’t you stick with one show for a longer time?’ It made me seem like I wasn’t dedicated or focused, that there was something wrong and I was getting fired, when they didn’t realize that these shows open and close like a circus. It’s just a very different world that recruiters don’t understand.”

That may be changing. Barry Winkless is Chief Strategy Officer of Cpl Group, a multi-national human resources and recruitment services firm headquartered in Ireland, and also head of its Future of Work Institute. In both those capacities he’s seen that some of the freshest thinking comes from people with experience outside a company’s core discipline.

“What we’ve recognized in the Future of Work Institute is the importance of bringing unexpected knowledge into existing domains. And that comes from diversity of background and diversity of capabilities,” said Winkless in an interview. “So when we talk about this idea of untapped potential, it’s important that we move beyond the confines of the CV, the confines of a resume. Genuine skills-based organizations are still in their infancy, but for me this is a no-brainer—bringing new competencies into unexpected places.”

Artists at play—serious value for startups

Who benefits from those with an arts background? With several years experience in tech, and seeing where their colleagues from Artists Who Code are thriving, McCreary and Ricafort McCreary feel that artists bring immediate value to young companies and new product teams.

A sense of play, something that artists actively cultivate throughout their career, can be just what’s needed in start-up environments. “If you’re working on a newer product, it’s helpful to have a visual and creative sense and be used to this idea of play,” said McCreary. “A good engineer battle-tests everything and wants to poke holes in arguments, which is great for solidifying your position. But there are times, especially when an idea or a product is newer, when the ‘yes and’ mentality is more helpful—the improv, brainstorming and play mentality.”

With a computer science degree or coding bootcamp certificate in hand, a musician or actor may be skills-indistinguishable from any other beginning software engineer, but companies shouldn’t overlook the intangibles that come from years on the stage.

For instance, Ricafort McCreary shares her enthusiasm for documenting code, a necessary but under-loved aspect of software engineering. Her years of acting and dancing—conveying a narrative in words and movement—gave her the tools to make that an essential part of her job. “At my company I started to write a lot of documentation for myself. And because I tell it as a story, with images, people started to find my documents really useful. So my team embraced it and that led to a larger project where I created our onboarding documents for new engineers.”

Software engineer and dancer/actor Catherine Ricafort McCreary writing code. Photo credit: Catherine Ricafort McCreary

“The life experience that comes with being a professional artist is that we have qualities that many of the fastest growing startups are looking for—like being scrappy and wearing different hats,” continued Ricafort McCreary. “If you’ve ever created your own one-woman show, you’ve written the script but you’ve also taken on the role of producer and director and hiring manager for the musicians. So if you take all of that, put it into an engineering role and then you ask us, oh, how would you creatively solve this problem? Just give us a little bit of room. There are so many ways we can add to the skills of writing code.”

With hard-to-find qualities, everyone is responsible for taking a chance

Beyond philanthropy, corporations and the arts are worlds that rarely interact. They don’t know each other and they don’t understand each other. So who makes the first move when it comes to hiring—and how?

From working with HR professionals, Wendi Safstrom understands that the commitment to take a chance on employees with diverse backgrounds has to come from the highest levels. “This starts at the top,” said Safstrom. “It’s got to be a dedication from the CEO and C-Suite—which includes HR—to say, we care about these pools of talent. We find them incredibly valuable. They bring skillsets that are otherwise difficult to find.”

But leaders in the arts need to do their part too. Barry Winkless would like to see more attention paid to helping artists generalize what they learn in their craft, and knowing their value in other walks of life.

“How can we make our people sustainable?” That’s the most important question, according to Winkless. “How can we make sure that we are giving them the mindset, the tools, the coaching well in advance of the challenges they’re going to face? It’s up to arts leaders to make sure their people can be sustained, within the arts and beyond the arts.”

Winkless, a musician himself, points out that this is not a criticism of the artistic life. Rather, it prioritizes artists—flesh and blood human beings who should have agency to apply their prodigious skills and experience across the economy.

“I think there’s a bit of growing up needed here, a shift in mindset,” reflected Winkless. “There’s a gargantuan opportunity in the arts world to take this, grab it, and be leaders in it. Surely, that’s also the role of a modern organization—to make an individual; not just employ them, but transform them and make them more sustainable.”

Barry Winkless speaking at the Anchor High Summit, Derry-Londonderry, Northern Ireland, May 2023. Photo credit: Barrry Winkless

Understanding our humanity in an age of AI

There is a future of work, perhaps not far off, where a prized resume—the right degree from the right school with the right kinds of experience—no longer guarantees success. As artificial intelligence and automation remake the landscape in so many industries, having a deep knowledge of what makes us human may come to be the most sought after quality.

What is the dramatic arc of a story? How do you feel another’s emotions, or harness your own? Where do you find beauty in the mundane and everyday? No one asks these questions in a job interview. It’s too bad, because the answers might reveal capabilities that go far beyond the ordinary.

“I hear recruiters and hiring managers complaining how hard it is to find good candidates, and I also hear artists complaining about how hard it is to get their foot in the door and have an interview that goes well,” said Ricafort McCreary. “But if I can just do a little bit of work to translate—on both sides—they are thrilled to find each other. It’s not like, oh, I have to let in these artists into my interview space. No, it’s in your interest. They usually nail it. And once they’re in the door and you have a different pair of glasses on to see what they can do, you’re like, why didn’t I know that you were here this whole time?”

—

Published here on Forbes.com

January 10, 2024