Still image from "Sunset Boulevard," SIGGRAPH 1997. Photo credit: Jon Winet

Thirty years ago, Rich Gold, a researcher at Xerox PARC (Palo Alto Research Center) wandered into engineer Scott Minneman’s office. He didn’t knock—office doors at PARC were hardly ever closed. “I’ve got a crazy new idea,” Minneman remembered Gold telling him. “Do you want to help me figure it out?”

Gold, who died in 2003, had been an artist, musician, and toy and computer game designer. At PARC he worked in the Ubiquitous Computing lab, tasked with bringing to life a vision of interconnected devices—progenitor of what is now called the internet of things. He was also something of a provocateur.

What Gold wanted to explore with Minneman was the creation of an artist-in-residence program—a humanist and aesthetic presence in this temple of cutting-edge technology.

Art was not foreign to PARC. Basic computer research into graphics, animation, and user interfaces attracted scientists with a creative sensibility. Many of the engineers walking the halls were talented musicians and new media artists. A few years earlier, Mark Weiser, PARC’s Chief Technology Officer, had invited artist Natalie Jeremijenko to work with his team at PARC, a collaboration that expanded their thinking about the uses and significance of ambient technology.

But Gold was looking to go from casual and “one-off” to a steady presence at PARC for the arts, and in doing so to reap the benefits of bringing together disciplines with different values and working methods—often exploring the same thorny but exhilarating problems.

That was the beginning of PAIR, the Parc Artist In Residence program. It’s been three decades since PAIR’s founding, and the program existed for only ten years, but its impact on the engineers and artists who participated continues to reverberate. For today’s corporate leaders, especially those grappling with the rise of machine learning and artificial intelligence, the story of art at PARC holds important lessons about the value of our humanity in a time of profound unease about the future of technology.

The shape of PAIR

In the late 1960s, engineer Billy Klüver of Bell Labs established Experiments in Art and Design (E.A.T.) to help avant-garde artists like Robert Rauschenberg and Andy Warhol realize their creative vision. This was fruitful teamwork, but it was more assistance than collaboration; an artist would approach E.A.T. with a technical problem, and an engineer from Bell Labs would solve it for them.

Rich Gold wanted something else for PARC—a residency that put artist and engineer on the same level, with an outcome where both disciplines would be changed from the experience. As he wrote in the book “Art and Innovation” published by MIT Press, “PAIR is a project not for creating wonderful art or exciting science—because we are dealing with highly skilled, talented, and motivated people these things almost always happen—but for creating better artists and better scientists.”

The RED (Research in Experimental Documents) group at Xerox PARC. From left to right: Maribeth Back, Anne Balsamo, Scott Minneman, Dale MacDonald, Steve Harrison, Rich Gold, Mark Chow. Photo credit: Anne Balsamo

Every PAIR collaboration began with matching. A committee of San Francisco curators unaffiliated with PARC selected the artists. With representatives from publishing, theater, music, new media and the traditional arts, the committee brought a diverse perspective on who in the Bay Area arts community would thrive in a research environment. “That was a smart thing,” said Dale MacDonald, a former PARC scientist, in an interview. “It kept us from picking our friends.”

MacDonald, now Associate Dean of Research and Creative Technologies at the Harry W. Bass Jr. School of the Arts, Humanities, and Technology, and Scott Minneman, now Professor in the MFA Design program at the California College of the Arts and Affiliate Researcher at the Institute for the Future (IFTF), were paired with new media artists Jon Winet and Margaret Crane.

How long should they work together? At the start, six months seemed like a reasonable amount of time to think up and execute a project. However, it took nearly that long to understand one another, learn how best to communicate, and forge a shared creative process.

“We were asking questions like, ‘What is your art? Why are you doing this stuff? Or what is your research and why are you interested in it?’” recalled Minneman in an interview. “Dale and I would wrap our heads around what Jon and Margaret were trying to do. It became very much a melting pot of ideas and practices and techniques.”

For Minneman and MacDonald, Winet and Crane, six months stretched, ultimately, to six years. During that time they collaborated on a series of multimedia productions that examined the artistic, technical and interactive possibilities of the early web.

There was “General Hospital,” a website that invited its viewers to participate in a digital commons around the issue of mental health. “Accommodations” explored the subject of home with a run-down but networked and computer-filled trailer in the University Trailer Park in Goleta, California. “Conventions” presaged the collision of politics and social media with real-time virtual commentary on the 1996 Republican and Democratic conventions. “Eliza Project,” inspired by Joseph Weizenbaum’s Rogerian therapy program, anticipated the experience of interacting with a ChatGPT-like intelligent agent. And “Sunset Boulevard” engaged the driving public—via their wireless key fobs and garage door openers—to change the narrative of a video soap opera showing on a pair of giant screens at the intersection of Sunset Boulevard and Doheny Drive in West Hollywood.

Margaret Crane, Scott Minneman, unknown, and Jon Winet at “Accommodations." May 1996. Photo credit: Dale MacDonald

While Crane, Winet, Minneman and MacDonald worked as a group, PAIR also had other models. Forms of collaboration were left to the artists and scientists—with no interference from the management at PARC. “They could drink beer together for a year for all I cared,” wrote Gold in his autobiography, The Plenitude. “The important thing was that it was together.”

Video artists Jeanne C. Finley and John Muse were paired with the Work Practice and Technology (WPT) area at PARC, a team of anthropologists and computer scientists studying automation and the interaction of humans and machines in the workplace. Instead of collaborating directly, these artists and researchers decided to run their projects in parallel, each under the curious and watchful eye of the other.

Both groups used video as their means of documentation—and this gave them a common language. Lucy Suchman, then Principal Scientist and Manager of WPT at PARC and now Professor Emerita in Anthropology of Science and Technology at Lancaster University UK, remembered lively conversations about claims of realism in video and what it meant to tell stories about people’s everyday activities. “We learned an enormous amount from Jeanne and John—having them in our space, looking at each other’s work and talking about it,” said Suchman in an interview. “There was a lot of cross-influence.”

For Suchman, the freedom to work in parallel with their matched artists ensured that they didn’t force a collaboration. Each side of the pair had the space and time to discover their new colleagues. “It was the kind of residency that allowed us to experience creative work in progress. And that really transforms your understanding of what art practice is.”

Homo Ludens—man at play

In an environment of cutting-edge technological invention—Xerox PARC was birthplace of the laser printer, ethernet, computer mouse, graphical user interface, and object-oriented programming—artists were a meaningful, if incongruous, presence.

They reinforced the boundary-shifting and slightly transgressive creativity that had put PARC on the map two decades before. And they brought with them a sense of play.

In their daily walks through the facility, PARC scientists were bound to encounter “Live Wire” by artist Natalie Jeremijenko, a red plastic cable suspended from a hallway ceiling that jerked, turned, and spun in response to the ethernet traffic on PARC’s network.

Some of the researchers who assisted Jeremijenko were embarrassed to be involved in something so silly, but others, especially CTO Mark Weiser, found it insightful. As recounted in John Tinnell’s “The Philosopher of Palo Alto: Mark Weiser, Xerox PARC, and the Original Internet of Things,” Weiser believed that art like Jeremijenko’s could ask wordless questions about the pervasiveness of technology in our lives. If nothing else, a twitching and twirling “Live Wire” made it impossible for anyone at PARC to miss the facility’s heartbeat, an otherwise invisible ebb and flow of digital information.

Scott Minneman, Dale MacDonald, and Anne Balsamo. May 2002. Photo credit: Scott Minneman

“You push the rules, bend them—even break them,” said Anne Balsamo, former Principal Researcher and Interaction Designer at Xerox PARC, and now Distinguished University Professor at University of Texas at Dallas. It’s an ideal way to invite serendipity, she explained in an interview. “You’re using materials in ways they’re not intended to be used, or you put things together that aren’t supposed to talk to each other. It’s a disregard for the conventions that shut down ideas and thinking and creativity.”

According to John Seely Brown, former Director of PARC and Chief Scientist at Xerox from 1992-2002, the spirit of Homo Ludens was central to PARC’s research culture and community of practice. “An ability to see something in a new way is key to art, but also key to breakthroughs in science,” said Brown in an interview. “If you can honor the white space between disciplines and learn to play with it, then suddenly art seems obvious.”

How much is it worth?

Those who worked at PARC often referred to Xerox as “the mothership,” a corporate overseer 3,000 miles away in Rochester, New York. That distance, psychological as well as physical, gave scientists and artists the freedom to pursue their hunches without needing to show an immediate product connection or return-on-investment. It also meant that they could assess the value of being together in strikingly different ways.

For many of the PAIR artists, the technology available at PARC alone was a treasure-chest. Large format color calibrated printers, custom laser cutters, non-linear editing systems—these were machines that weren’t available to the public, or even at most universities. And if something an artist needed for a project didn’t exist, there was a good chance that a PARC scientist could invent it.

Whether or not they realized it at the time, those scientists were also changed by seeing, interacting with, and creating art at PARC. “There were engineers who would say, ‘That art program is nice to have around, but it doesn’t apply to me,’” said Dale MacDonald. “And some of those people were later surprised to learn how interesting it was, and that it did have something to do with them. For Scott [Minneman] and me, it pushed our research along and opened new venues to thinking about communication and media in ways we continue working on today.”

But what about the return-on-investment that Xerox was most interested in—a new technology coming out of PARC that served the bottom line? It’s the secret dream of corporate artist-in-residence programs—that an artist and employee work together to create something that proves the program’s value, beyond any shadow of a doubt.

In 1997 the team of Winet, Crane, MacDonald and Minneman showed off the new technology behind “Sunset Boulevard” at SIGGRAPH, the annual conference of computer graphics and interactive techniques. Jon Winet, now Professor Emeritus at the University of Iowa School of Art & Art History, a member of the university’s Public Policy Center, and visiting professor at the University of California History of Art Department, recalled how a vice president from Disney appeared at PARC soon after the conference and asked for a demonstration.

Jon Winet, left, on the set for “Sunset Boulevard.” Photo Credit: Scott Minneman

“I happily explained it to the best of my knowledge,” said Winet in an interview. “And he said, ‘We’ll be back tomorrow.’ So the next day he and 25 associates were there. We contacted PARC and said, Disney seems fantastically interested in this project. Then the lawyers got to work. As quickly as they could, they wrote a patent and it was approved.”

The patent had broad coverage over individual control of large format displays using technologies like cell phones and key fobs. It’s now a common interactive experience in stadiums and other public entertainment venues, but Xerox chose not to enforce the patent or explore what was possible. “That was a moment where you’re like, why isn’t the company going after this?” said Minneman.

The legacy of PAIR

The PAIR program concluded in 2003 with a public exhibition called “The Art of the Book in a Digital Age.” By that time it was clear that Xerox was not interested in following up on most of the non-printing breakthroughs that came out of PARC—whether the interactive display tech pioneered by the PAIR team, or any number of software and hardware inventions that companies like Apple, Microsoft and Adobe ultimately brought to market.

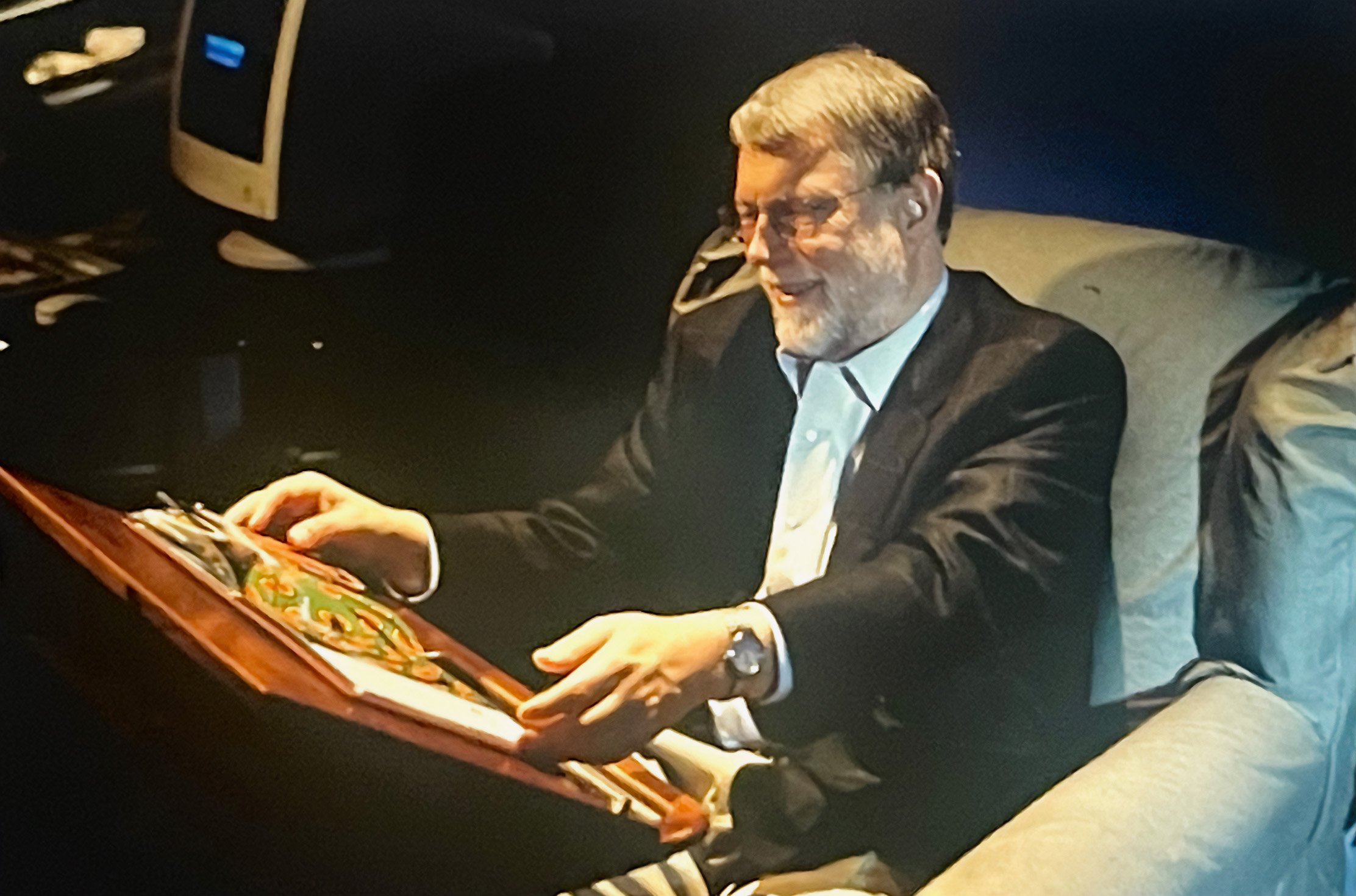

John Seely Brown with the Listen Reader at XFR (Experiments in the Future of Reading) exhibit. February 2000. Photo credit: Deanna Horvath

PARC’s founding charter was to “create the office of the future.” How best to do that? Be curious, ask good questions, cultivate the people and places where new ideas bubble up. These values animated PARC right from its founding. They were the reason so many talented people wanted to work there.

Rich Gold understood this when he shared the idea of an artist-in-residence program with Scott Minneman in 1993. But in the years since the end of PAIR, the need for a humanist and inquiring presence in corporate environments has only become more acute.

Can artificial intelligence be truly creative? Do we understand that most-human of abilities well enough to understand ourselves? Is there a domain of imagination and emotion that can’t be accessed by machines? Companies need people who can explore these issues from a fresh perspective.

“We are entering a new world that has existential crises,” said John Seely Brown, looking to the future. “To be able to think creatively about how to handle them is the most critical job. And most of us have no understanding how much our accepted wisdom is out of keeping with where the world is going.”

—

Published here on Forbes.com

October 27, 2023