Pexels: photo by ClickerHappy

Between the rising unemployment rate, a dramatic increase in corporate AI spending, and Merriam-Webster’s choice of “slop” as its word of the year, what we’re absorbing in these final days of 2025 is giving many Americans anxiety about their careers in 2026.

Surprisingly, one of the most maligned groups, arts and humanities graduates, is well positioned to thrive in this disrupted environment. Here are five ways they can take advantage of new realities in the workplace:

1. When AI makes information a commodity, those with an unusual perspective gain extra value.

On a recent episode of Microsoft’s WorkLab, EY Global Consulting AI leader, Dan Diasio, shared an anecdote about his company’s early experiments with artificial intelligence. In a series of exercises, EY clients were guided in working with generative AI to design a new snack product. While it was the client experience that mattered, Diasio noticed that the end products were all eerily similar. After leading hundreds of these exercises he saw the same ingredients, recipes, packaging and marketing plans over and over again. “Like if this stuff were to come true, we would have a global shortage of matcha and monk fruit everywhere,” he said.

For Diasio and other perceptive leaders, it’s human insight that remains the differentiating factor. When every company is using the same models in the same ways, having employees with deep wells of unique experience is like money in the bank. “AI makes it very easy to produce something good, but it commoditizes the output,” explained Diasio. “In a lot of ways it raises the floor, but it doesn’t raise the ceiling.”

What raises that ceiling? Cultivating diverse talent—those who come from unusual backgrounds, who see the world differently than everyone else.

2. If you want fresh talent, don’t keep it a secret.

Unless hiring for difference is a clear and stated policy, that kind of diverse talent doesn’t arrive on its own.

For example, the multinational technology consulting company, Cognizant, is very public about its interest in humanities graduates. Cognizant CEO Ravi Kumar S recently shared with Fortune that in his opinion, AI will empower those more able to find and define problems, not just solve them. “Intelligence is not the asymmetry. Applying intelligence is the asymmetry. Start to focus on interdisciplinary skills,” he said.

And earlier this year Neal Ramasamy, Chief Information Officer of Cognizant, authored an Information Week article in which he explicitly advocated for a broader approach to identifying new talent, suggesting that IT recruiters add liberal arts schools and music conservatories to their regular campus visits.

“We also need to recognize that the most valuable skills don’t always show up on a resume,” wrote Ramasamy. “How do you measure the ability to see a new solution that nobody else considered? Or the capacity to understand what a user is really asking for, even if they can’t quite articulate it? These are the skills that will matter most, even if they don’t fit neatly into a job description.”

There’s a natural bias against hiring for difference, whether by AI algorithm or human screener. We all feel more comfortable around people like ourselves. They have similar histories, use similar language, and we know how to judge their accomplishments.

So how do we lean the other way? By modeling another approach from the top. Senior people, who understand the strategic importance of cognitive diversity, need to make it safe for lower level screeners to take a risk. Otherwise, the prospective employee who looks and sounds different will never stand a chance.

3. “Humans-in-the-Loop” only works if you use the right humans.

We are entering an era of work where generating huge amounts information is easy, fast and cheap. But that abundance comes with two serious challenges: First, is the information true—can we stake our reputations on it? And second, what does it mean?

Having people trained in close reading, critical thinking and interpretation working alongside programmers and engineers will be essential in the very near future. Graduates in disciplines like history, literature and philosophy are comfortable with ambiguity and contested meaning; they know how to detect bias, contradictions and narrative gaps in large blocks of text.

As regulations like the EU Artificial Intelligence Act are phased in over the next few years, companies are going to have to demonstrate compliance. And they will need employees who can help them do that. For instance, Article 14 of the EU AI Act, “Human Oversight,” requires people-in-the-loop, especially around issues like safety and human rights.

Increasingly, those employees will be graduates of programs like the Certificate in Ethics and Artificial Intelligence from Carnegie Mellon, a joint program between its School of Computer Science and College of Humanities and Social Sciences; or the Ethics of AI, offered by the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign Department of Philosophy; or the Certificate in Artificial Intelligence: Ethics and Society from American University in Washington D.C., among others.

AI governance is no longer abstract. Unless the ethics and safety concerns of a skeptical public are taken seriously by companies, a growing backlash risks undoing hard won gains.

4. Customers and employers will pay a premium for advanced social intelligence.

McKinsey’s Global Institute 2025 jobs and automation report, “Agents, robots, and us: Skill partnerships in the age of AI,” makes the startling claim that our current robotics and AI technology could automate more than half of all U.S. work hours, representing, “...about 40 percent of total U.S. wages.”

What remains? Manual work that can’t yet be done by robots, and activities that require nuanced interpersonal skills. These particular qualities—social and emotional intelligence—are the hardest to teach in workshops or acquire on the job. They require learning by doing and years of practice.

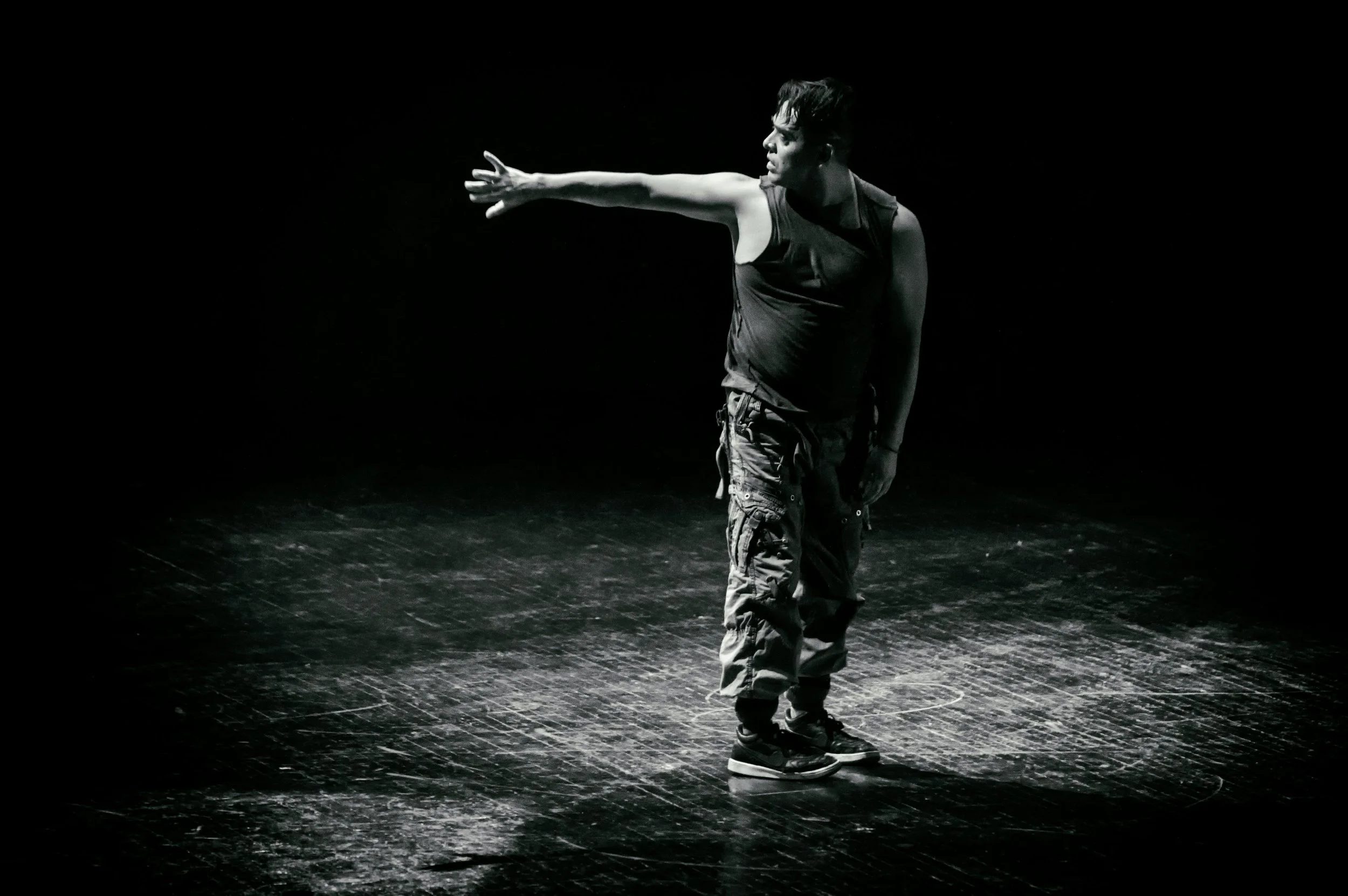

Fortunately, there is a group of people who have already put in the time and hard work. Performing artists—actors, dancers, musicians—are trained in communication, presence, improvisation, and collaboration under pressure.

Pexels: photo by Genaro Servín

Do you need an employee who can read the room, pick up non-verbal cues, smoothly improvise a presentation? This is what actors do. They consider a character’s motivation. They practice identifying with someone who may look or sound very different than themselves.

Are you designing a robot that interacts with customers? Add a dancer or choreographer to your team of engineers. They’ve been studying how humans move since childhood. In fact, a new field called choreorobotics is already formalizing this collaboration.

Is teamwork more than a slogan for you? Musicians take collaboration to the highest level. They lead and respond to colleagues in real-time, usually without exchanging a single word.

Looking for presence in front of an audience? Performing artists live for the stage—even if it’s a corporate boardroom—and they don’t let butterflies freeze them up; they know how use nerves to their advantage.

Recruiting people with a serious background in the performing arts is a huge opportunity, but it’s not without challenges. Artists are not taught how to articulate their skills, and corporate mentorship is hard to find. Want to move from stage to office? More often than not, you are on your own.

5. The arts and humanities will continue to be underfunded, but that’s also driving innovation.

This past year saw an acceleration of cuts to the arts and humanities across higher education. From a $10 million cancellation of previously awarded grants in California in April, to a major restructuring at the New School in November, liberal arts institutions are feeling unprecedented financial and political pressure. That will likely continue into 2026.

But strain and crisis also leads to bold new ideas. More than a few schools are rethinking how the humanities can serve our current needs as a society and economy. From Purdue to Brandeis to Georgia Tech, universities are positioning a study in the liberal arts as essential for thriving in a world saturated by AI.

Virginia Tech is going one step further, offering humanities training to mid-career leaders who want a very different kind of professional development. Now in its third year, the Virginia Tech Institute for Leadership in Technology is a highly selective fellowship for executives across a range of industries like finance, government, law, software, aerospace and consulting.

Founded by entrepreneur and former Google, Twitter and YouTube executive, Rishi Jaitly, the institute has an online and in-person curriculum that guides participants in reading, listening, and conversation with those of opposing ideas and sensibilities.

It is only a year in length, but the program has had a lasting impact on its participants. Danielle B. Ruderman, Amazon Web Services Senior Manager and a fellow in the inaugural class, shared her experience in a blog post on the institute’s website.

“...we do not need to wait for saints or zealots, we don’t need to be perfect ourselves or at the top of the industry to make a difference,” wrote Ruderman. “If the measure of a society is what it does for its most vulnerable citizens, is the measure of a tech leader what we do to improve the lives of those most at risk in our society? And if so, how do we—ordinary flawed people—apply this lesson as humanistic leaders in tech today?”

Look forward by looking back

On the morning of December 7, 1941, the United States Pacific fleet in Pearl Harbor was destroyed by Japanese aircraft in a surprise attack. This was not only a military disaster for the United States, but a colossal failure of imagination and intelligence.

Photo courtesy of the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

To address that failure, the U.S. government created the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), which then turned to an unlikely pool of new recruits—scholars in the humanities, social sciences and the arts.

This story, as told by Elyse Graham in “Book and Dagger,” describes how bookish and bespectacled professors of history, literature, economics and anthropology were transformed into top-notch analysts and secret agents.

“The library rats of the OSS were able to do brilliant work in intelligence because they had expertise in fields that their enemy counterparts didn’t,” writes Graham. “They approached problems differently. They saw military intel in newspaper society columns, maps to unfamiliar cities in phone books, potentially devastating enemy vulnerabilities in humble items like ball bearings. They turned out to be excellent at what intelligence actually entails: innovation.”

We are not at war today, but the actions of the nascent OSS in 1941—turning overlooked and unappreciated talent into a potent advantage—should be a timeless lesson.

Who will have value in this new age of bots and automated agents? Perhaps not experts in vibing, prompting or optimization, but those who have grappled most with what it means to be human.

—

Published here on Forbes.com

December 29, 2025